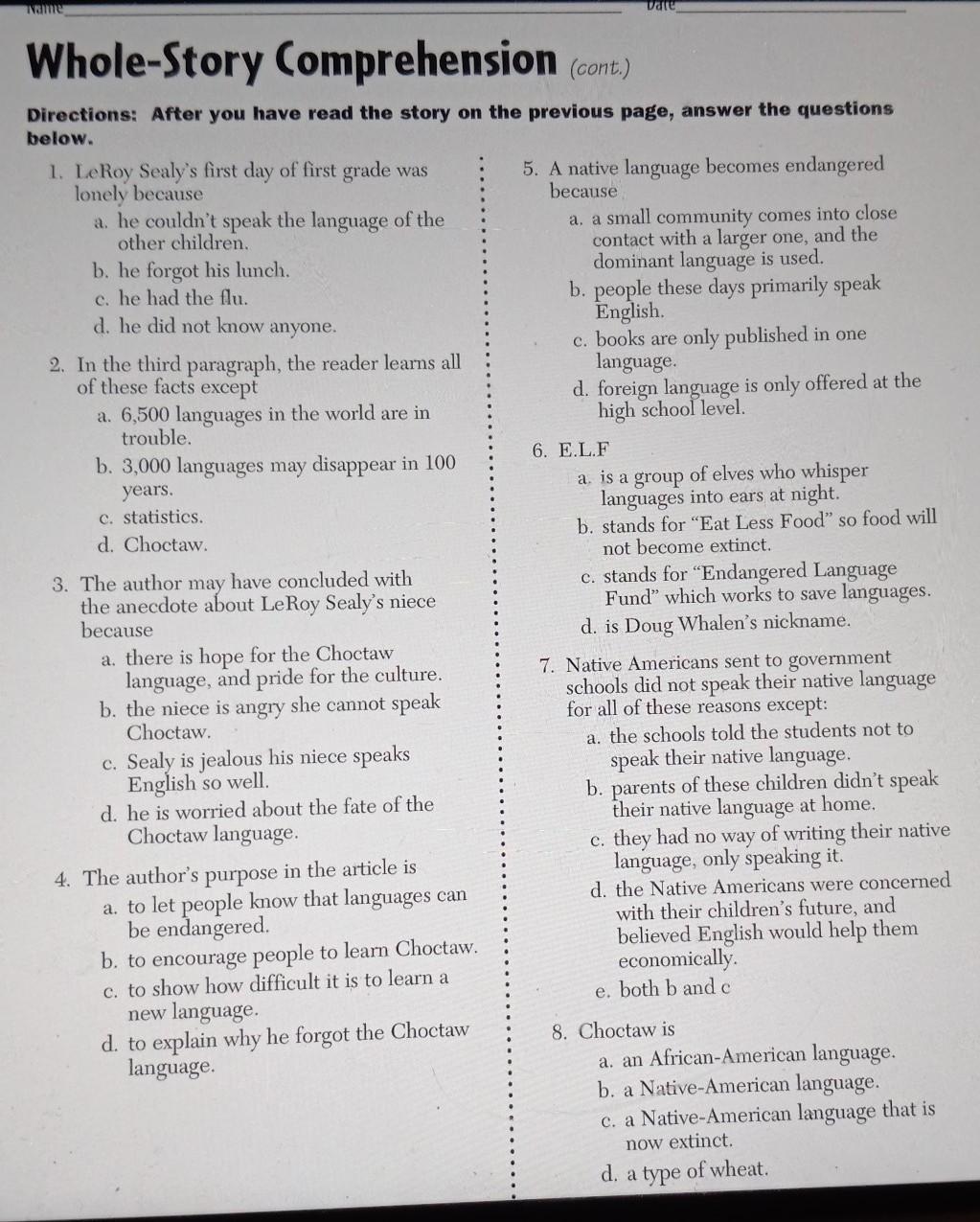

the kids in his class and he couldn't understand a thing they were saying. "I was pretty much alone because I couldn't communicate," says Sealy, a Choctaw Native American. "I didn't learn English until starting school." Sealy knew only the Choctaw language, and no one in his class could speak it. Sealy is now a professor of Choctaw at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. He still speaks Choctaw, as do about 12,000 people, but he is worried about the future of his native language. Choctaw is on the endangered-language list. When you hear the words endangered or extinct, you may think of rhinos, tigers, and other wildlife. But languages can also become endangered and extinct. Linguists, people who study languages, say about half the world's 6,500 languages are in trouble. Some have fewer than five living speakers, and nearly 3,000 may disappear in the next 100 years. Concerned linguists are working to save endangered languages. One group doing this work is the Endangered Language Fund (E.L.F.), which just awarded $10,000 for 10 language- preservation projects. The money will be used to make recordings of languages such as Maliseet, Juskokwim, Choctaw, and Klamath, so their words won't be lost forever. How does a language become endangered? “The most common cause is probably that a small community comes into close contact with a larger one, and people begin using the dominant language," says linguist Doug Whalen, president of the E.L.F. Better technology and transportation have spread more common languages, including English, across the planet. Native languages are used less. In Australia, for instance, only about 10 speakers keep the Jingulu language alive. Most Australians speak English. Sealy says governments have also hurt native languages. “Native American children sent to government schools in the 1950s and '60s were told not to speak their native languages either, believing that English would help them economically in life. This caused many languages to be lost." Why should we care? “Every language has its way of expressing ideas about the world," explains Whalen. "When a language dies, we lose that insight." Many endangered tongues face another threat: young people who have no interest in speaking the language of their ancestors. Sealy hopes young Native Americans will learn to value their cultural heritage and language. "My niece, who's in fourth grade, is learning Choctaw, and although she mostly speaks English, she understands Choctaw when we speak with her," says Sealy. “We encourage her because the younger generations will be the ones to carry the language into the 21st century."